How Making Our ML Models Worse Helped Us Win A Datathon

From the 7th to the 13th of March, I was part of a team of Cambridge first year students who participated in the Europe Datathon for the Citadel Data Open 2022. The datathon, organised by Correlation One and Citadel, was a week-long competition in which we were given a large dataset to analyse. Teams were expected to formulate a research question, process the data and present the findings in a report by the end of the week.

After receiving an invite from a friend to team up for this datathon, I thought of this datathon as simply a fun opportunity to gain some more experience with data science tools in Python. After all, I had never used these tools in the wild before.

There was one specific day of the datathon in which we had made our first breakthrough.

Something’s not quite right⌗

It was the fourth day of the datathon. We were investigating potential factors that lead to a late shipping order. With our primitive tools, we had not found anything within the provided dataset.

Junhua had the idea of training a machine learning model on the remaining rows of the dataset to predict whether an order would arrive late. We did not have to have the model be highly accurate; all the models had to do was to provide us with a launchpad from which we could more efficiently explore correlations in the data.

After some quick experimentation, he came to me, completely dumbfounded, with a 94.8%-accurate random forest model.

Lesson 1

Always question when a machine learning model performs way too well.

Getting an almost 95%-accurate model, in most cases, would be an amazing achievement. However, in this case, we had a seed of doubt in our minds that it was too good to be true. How come we could not find any correlation in the data manually, whereas a machine learning model had found such a strong correlation effortlessly?

At first, I thought that it was simply a quirk of on-time orders having far more entries in the dataset than late orders, that the model could always predict “On-time” and achieve high accuracy. However, there were actually a balanced amount of entries that were late and on-time. How could this be?

We saved the model and ran a permutation feature importance test on the model with the validation data, which told us approximately how much each feature of the entry contributes to the model’s prediction accuracy.

Late Delivery Risk 0.460359

Days for shipment (scheduled) 0.113837

order date (DateOrders) 0.035250

Customer Id 0.033855

Order City 0.017579

Order State 0.012757

...

…huh? Replacing “Late Delivery Risk” from the dataset with garbage reduces the accuracy of the model from almost 95% down to 48%??? Also, what were these other rows? How was the ID of the customer contributing to the accuracy of the model?

Okay, wait, what was “Late Delivery Risk” even supposed to be again?

Late Delivery Risk: int64

Categorical variable that indicates if sending of the order is late (0 indicates shipment was sent on time; 1 indicates shipment was sent late)

Oh. This row literally tells you whether an order was late, so the model could just read from that field and output the answer. It seems that we forgot to remove this from the model’s input features.

Okay, that was embarassing. To avoid encoding the label into the features indirectly, we decided to stick with only the features that would be known to us before the delivery. In the next attempt, we trained a Naive Bayes model instead, as the random forest model had taken a while to train. That should solve the issues, right?

It did not solve the issues⌗

Accuracy: 0.879171128411426

order date (DateOrders) 0.181489

Days for shipment (scheduled) 0.087223

Customer Id 0.042150

Order City 0.007826

Order Item Quantity 0.000150

Order Department Id 0.000110

The model still had a rather high accuracy and the permutation importance test was outputting some strange results. It seems that this model mainly relies on the order date and time to predict whether the order was late or not, which makes little sense, as the data analysis we performed in the previous days were not able to identify much global seasonality.

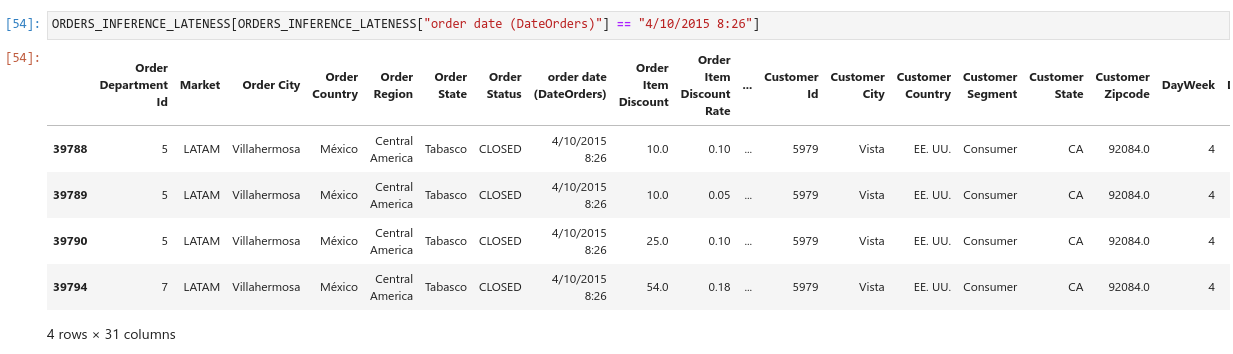

Was the model somehow overfitting? If so, how was it doing so well on the validation data? Let’s bring up the data for a specific day.

So, multiple entries with the same delivery details but different pricing are grouped by the same date and time, and the delivery status is the exact same. This meant that there were essentially duplicate entries in the dataset.

We realised that we had made yet another mistake in splitting the training and validation data randomly. Since most of the entries in the validation set had duplicates in the training set, the Naive Bayes could memorise the answer simply by looking up the date and time of the order.

Lesson 2

Be very careful when splitting training and validation data randomly.

To avoid this issue, we used the most recent 20% of the dataset as the validation dataset and the remaining 80% as the training dataset. Running the model, we now have

Accuracy: 0.6411020750730761

Days for shipment (scheduled) 0.098857

Order City 0.013052

Order State 0.001650

Order Country 0.000660

Order Item Discount 0.000614

Order Status 0.000457

This seems a bit more reasonable. We eventually investigated the “Days for shipment (scheduled)” and “Order City” features with chi-squared tests and found that they did indeed contribute to the lateness of the delivery.

Conclusion⌗

After numerous other breakthroughs and contributions made by all of the team, we spent the entirety of the last day writing up a 5000-word report detailing all of our findings. Then, the next day…

We won first place.